ENARADA, New Delhi,

By AJAY N JHA

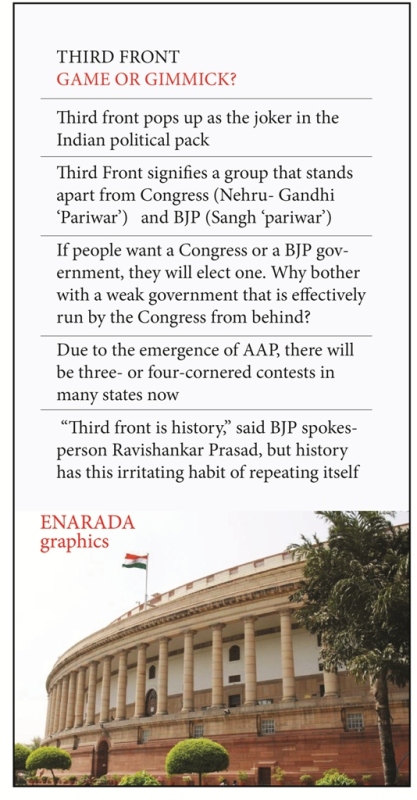

Come Parliamentary elections and the Third front pops up as the joker in the Indian political pack and starts selling itself up as a serious alternative to the two national parties—Congress and the BJP. The basic premise is its claim of being more inclusive, bringing into the public fold social groups neglected or oppressed by the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party. Interestingly, this rag-tag group that has been emerging and re-formatting itself with near-decadal precision since 1967.

The rise of these parties was part of a process of the broadening of Indian democracy, bringing into the public sphere middle and lower castes, religious minorities and tribals in their own right. Yet this concept of ‘broadening’ could not really culminate in deepening of democracy, empowering these traditionally subordinate groups. On the contrary, it has become the cultural equivalent of the failed trickle-down theory in economics, bringing immediate benefits to the elite amongst them, entrenching some at the cost of others and widening social disparities further.

“Each of them has slept with almost everyone else, supported policies across the spectrum, bonded with reformists, communists, communalists, secularists, pseudo-secularists, appeasers, all the various other terminological curiosities that pepper the Indian political glossary” Said a political commentator.

In the present context, it is called a Third Front because the First and Second Fronts are, respectively, led by the Congress of Sonia Gandhi and Manmohan Singh and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of the Advani-Rajnath Singh-Narendra Modi triumvirate. In other words, it is a different “pariwar” from Sangh- BJP and Nehru- Gandhi ‘Pariwar’.

The Third Front signifies a group that stands apart from the Congress and BJP. However, by bringing together any one and every one regardless of their history, ideology or even program, who, for various reasons, is opposed to the Congress or the BJP.

Ironically however, almost all the constituents of the Third Front have in the past been part of the alliances led by either the Congress or BJP. CPI(M) and CPI too supported the United Progressive Alliance until they parted company with the Congress over the Indo-US nuclear deal and voted to oppose it along with the BJP.

The proposed ‘Third Front’ is currently expected to include the AIADMK, TDP, TRS, and JD(S); their big catch will be the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) of Mayawati if she decides to join them. This possibility is real only if it delivers her the post of the Prime Minister of India. Of course if either Congress or BJP need her, depending upon the election outcome, and offer her this position she would be just as ready to join hands with them and abandon the Third Front. But this can only be tested after the election. Neither Congress nor BJP will offer her that privilege in the pre-election period.

In essence the Third Front envisioned by CPI (M) and CPI is outright opportunist. What the Third Front will or can do can only be verified if they come to power, which at this stage seems highly unlikely. It is still a battle between the First (Congress) and the Second (BJP) Fronts. Some feeble-minded in the Third Front might feel that BJP is at the end of its rope and has no chance of coming to power. Hopefully the democratic and secular populace will not have any illusion on this account and do everything to deny BJP a victory in the forthcoming elections. Also, hopefully, there might still be sane elements within the CPI (M) and CPI, who would rather patiently build a progressive democratic front with a clear economic and political agenda and thwart the designs of their current leadership, which seem to be focused mostly on becoming a part of the government.

However, given the complexities of the Indian and South Asian political scene and the world- wide economic crisis, there is one respect in which a Third Front may still end up playing a worthwhile role, despite the opportunism of its progenitors. The political challenge that is most acute in India is to maintain a secular polity, while the larger problem in South Asia is for India to play a progressive and calming role in helping to defuse the crises that have enveloped its neighbours, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

The BJP led front is openly communal. The Congress presents a secular face publicly, but has tended to compromise with communalists on occasion. The left parties, by and large, are an avowedly secular force in Indian politics. As the leading force in the Third Front, they can be expected to provide a more determined challenge to any attempt to dilute the secular nature of the Indian state, than if they were junior partners in the Congress front. In the South Asian crises also, especially the one developing in Pakistan, a Third Front can help somewhat in pressuring the Indian government to follow a more independent policy less influenced by U.S. interests in the region.

The first example of the ‘Third Alternative’ was the National Front (Rashtriya Morcha) was a coalition of political parties, led by the Janata Dal, which formed India’s government between 1989 and 1990 under the leadership of N. T. Rama Rao as President and V. P. Singh as Convener. The coalition’s prime minister was V. P. Singh. The parties in the Front were: Janata Dal of North India, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam of Tamil Nadu, Telugu Desam Party of Andhra Pradesh, and Asom Gana Parishad of Assam and Indian Congress (Socialist). They were supported from outside by the Left Front and the Bharatiya Janata Party. The Leader of the Opposition, P. Upendra was a General Secretary of the Front at its formation.

In 1991, Jharkhand Mukti Morcha became a part of the front. The front got defunct before 1996 LS polls when NF tried to rope in both DMK and AIADMK resulting in the walking out of the DMK. In 1995 TDP also split with a minority faction siding with N. T. Rama Rao and the majority faction chose to side with Chandrababu Naidu. After NTR died of a heart attack in January 1996, Janata Dal stood by Rama Rao’s widow Lakshmi Parvathi while Left parties formed an alliance with Chandrababu Naidu.

After the 1996 elections, Janata Dal, Samajwadi Party, DMK, TDP, AGP, All India Indira Congress (Tiwari), Left Front (4 parties), Tamil Maanila Congress, National Conference, and Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party formed a 13 party United Front. H. D. Deve Gowda became the prime minister after both V. P. Singh and Jyoti Basu declined to become PM. He was later succeeded by I. K. Gujral. Both governments were supported from outside by the Indian National Congress under Sitaram Kesri.

In reality however, there is no such thing like a “Third Front” or a non-BJP, non-Congress front available to the voters of India in a Lok Sabha election. In fact, there never has been. There is a difference between a government led by a Prime Minister who is not from the Congress or BJP and a government which has nothing to do with the Congress or BJP. India has experimented with the former but never with the latter. In 1977, when Morarji Desai became the first “Third Front”, non-Congress (and indeed non-Jan Sangh) Prime Minister of India, he did so in alliance with the Jan Sangh (BJP’s precursor). LK Advani and Atal Behari Vajpayee were important members of the Cabinet.

In 1979, when he was felled and replaced by Charan Singh, another Third Fronter, it was done with the support of the Congress. Then in 1989, when VP Singh became Prime Minister of another Third Front (it was called the National Front), he was supported by not just the Left (the usual suspect in a Third Front) but by the BJP as well. His government fell after 11 months in office when the BJP withdrew support.

The Third Front experiment continued, with Chandrashekhar replacing VP Singh and the Congress replacing the BJP as the outside supporter. Needless to say it did not last. It didn’t take long for a Third Front to reemerge.

In 1996, what was left of VP Singh’s Janata Dal hoisted Karnataka Chief Minister HD Deve Gowda into the Prime Minister’s chair but the government an on the life support of 146 Congress MPs. When then Congress President Sitaram Kesri tired of Gowda replaced him with IK Gujral only to abandon him in 10 months’ time.

It isn’t surprising that voters have opted out of giving a Third Front another opportunity to rule, not least because it has always been a front run at the mercy of either the Congress or BJP, far from its rallying cry of being equidistant from both ‘national’ parties. In reality, it has always been a second front, formed opportunistically to either stop the Congress or to prevent the BJP from forming a central government.

In 2014, Karat and his friends have actually no realistic chance of laying claim to form a government in Delhi without the backing of Congress or BJP. As long as the Left is an integral part of the Front, it is only reasonable to assume that the motley group will expect to be propped up by the ‘secular’ Congress. After all, the Left backed the Congress in 2004.

But voters of India have become wiser and that is seen in their decisive mandate given to particular party in the State elections since 2010 starting from Bihar. If they want a Congress or a BJP government, they will elect one. Why bother with a weak government that is effectively run by the Congress from behind?

That is why the Third Front is a non-starter. There is no realistic chance of these eleven new found friends getting anywhere more than 100 Lok Sabha seats put together. They may cobble together another 50 or 60 but no more. After all, Mamata cannot be on the same side as the Left, Lalu can’t be on the same side as Nitish and Mayawati cannot be on the same side as Lalu.

The Third Front, like its constituents, is a reality only in the states where it is possible to form stable and lasting governments without the need for support either from Congress or BJP. There is a reason why the Congress and BJP alone are labelled ‘national’ parties. They have always been the powers that sat on the throne or ruled from behind. There is no Third Front except the one that periodically cooks in the imagination of a few over-ambitious politicians.

The most interesting aspect of the 2014 elections is that, despite the initial momentum gained by the BJP under Narendra Modi, its outcome is still unpredictable. This is largely because of two factors: the rise of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) in Delhi, and its plans to spread elsewhere; and two, the fear of Modi, which may drive unusual partnerships in some states (Congress-BSP in UP and Congress-RJD-LJP in Bihar). This means straight fights between the Congress and BJP will be restricted to Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhatisgarh, Rajasthan and Punjab.

In this case, a report data card published in The Economic Times says that with the BJP notching up fewer allies, the party may show a greater trend towards losing three-cornered fights if we assume that it will win more vote share in the south and east, but not too many additional seats. The data suggest that in 2009, the BJP won 51 percent of its straight fights, but only 31 percent of its multi-cornered fights. The Congress, on the other hand, won 55 percent and 58 percent respectively. In 1999, which was BJP’s comeback year under Atal Behari Vajpayee, the party won 68 percent of its straight contests and only 38 percent of its multi-cornered ones.

The Congress, though it lost badly, managed 31 percent in both cases. Does this mean that the BJP is disadvantaged in multi-cornered contests? The answer may have to be more nuanced that just what the numbers suggest. For example, the reason why the BJP seems to lose more in multi-cornered contests may be simple: its support is concentrated in the north and the west, whereas in the east and the south it may be losing most of its attempted contests, especially when it is not part of a strong coalition. Most of its losses as No 2 or No 3 in the race may be in these states.

In 2009, the BJP had no partners in the south and east, where the main contests were between the Congress and regional parties. It came a poor third, barring Karnataka. This year, with the BJP notching up fewer allies than before (though this may change closer to April-May), the party may, in fact, show a greater trend towards losing three-cornered fights if we assume that it will win more vote share in the south and east, but not too many additional seats.

On the other hand, a harder look at the data suggests something else: the sharp decline in BJP’s winning performance in multi-cornered fights starts from 1999 – where it won only 38 percent of such contests, and falling further to 32 percent and 31 percent in 2004 and 2009 – can be largely attributable to the party’s headlong tumble in Uttar Pradesh. UP was where the party won the most seats in 1998 (57), and this dropped steadily to 10 in 2009. In UP, from 1991 to 1998, the BJP was winning three- and four-cornered contests; after 1999 it started losing them.

In 2004 and 2009, moreover, the party’s key allies drifted away: in Andhra Pradesh, Chandra Babu Naidu took his own road with the Left (and lost) in 2004, while in Odisha, Navin Patnaik’s BJD dumped the BJP in 2009. Thus the BJP became the third party in these two states too. Apart from UP, the state in which three-party contests have really affected the BJP is Maharashtra – where the emergence of Raj Thackeray’s MNS has forced the Sena-BJP alliance to live with fewer seats than it could have won otherwise, given the relative unpopularity of the Congress-NCP alliance.

But what do the data suggest for 2014? Are there any pointers that the BJP must take note of? Due to the emergence of AAP, there will be three- or four-cornered contests in many states now. The key states to watch for surprise three-cornered results are Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana and Maharashtra. In Uttar Pradesh, if the Congress and BSP tie up for a seat-sharing arrangement, the resultant three-horse race could dent Modi’s appeal to some extent. But one could well see a three-cornered fight benefiting the BJP, for if the Congress ties up with Mayawati, its supporters could head for the BJP in larger numbers. So UP is again key to proving or disproving this three-cornered theory.

In Bihar, the emergence of a stronger Congress-Lalu alliance may end up depleting Nitish Kumar and his JD(U). So a loss for BJP seems unlikely. In Maharashtra, the Modi-Sena-RPI-Swabhimani Shektari combine looks likely to overcome the MNS’s spoiler gambit, though it is too early to predict this. AAP could be a factor in Mumbai and Pune, making the contest four-cornered. Karnataka is also three-cornered – Congress, BJP and JD(S) – but the chances are it could become a two-horse race with the re-entry of BS Yeddyurappa in the BJP.

The most interesting three-cornered fight could be in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh – where the BJP will probably enter the fight in alliance with one or two regional parties. This could give it the BJP a higher success ratio if it gains 3-4 seats in the bargain in each state. Chandrababu Naidu in Andhra, and PMK and MDMK are possible partners in Tamil Nadu. The three-cornered contest theory has not been tested against the fact that there is now a strong Modi pull-and-push factor in these elections. Three-cornered contests may have worked against the BJP in the past, but this time there is an additional “M” factor whose value we will discover only by the end of May, when the results are out.

Neither the Congress nor the BJP relishes the prospect of a third force jostling with their respective formations for political space. But however tenuous the idea of third front might be, none of the parties just cannot wish it away. “Third front is history,” said BJP spokesperson Ravishankar Prasad, but history has this irritating habit of repeating itself. Come 2014, the country might witness an alternative political formation to the UPA and the NDA.

The experiment has been disastrous with no such formation being able to provide a stable government. The United Front— an amalgam of 13 political parties— formed two fragile governments between 1996 and 1998 and there have been abortive efforts to stitch together parties incompatible with the Congress and the BJP ideologically and otherwise. But none has lasted. Conflicting egos and ambitions among leaders and pervading mutual mistrust ensured that the third front remained inherently unstable. But the idea won’t go away.

The reason is simple: There has always been enough scope for such a formulation in the available political space. Now that the Congress is shrinking across the country and the BJP has not been able to expand enough to capture the space for itself, the opportunity for the formation of a third front has gone bigger than ever before. That explains the sense of urgency in Samajwadi Party chief Mulayam Singh Yadav’s efforts to reach out to other like-minded leaders and parties. SP supremo Mulayam Singh Yadav. There was an inkling of the core of the front when Mulayam came together with the Left parties during the Bharat Bandh today and Telugu Desam Party chief Chandrababu Naidu hinted that a new combine was possible.

JD(S) chief Deve Gowda is likely to join the party at some point later. Forget the history of betrayal between the Left and the Samajwadi Party — the former has ended up the victim at least three times, all that seemed forgotten today. However, this is irrelevant in the context of the import of the alignment taking shape. Traditionally, the third front has been a configuration of anti-Congress, anti-BJP and Left-of-the-centre parties. This time, unlike earlier, there are a large number potential backers with enough potential to deliver the numbers for the front to sustain.

That probably explains why the Left despite its bad experience with the likes of Mulayam has started showing serious interest. “Mulayam should take the lead in the movement. He should take the initiative, both inside and outside the Parliament as he is the leader of the biggest party,” said CPM general secretary Prakash Karat. Senior party leader Sitaram Yechury also spoke about the need of a third front. He said people needed a political alternative based on policies. “We want non-Congress and non-BJP political parties to come together to give a political alternative,” he said.

The ground reality today is that since the third front remains an amorphous entity till the election results are out one can never be sure how it would shape up finally. But would it be a viable entity? Fat chance. The Left won’t go with Mamata Banerjee, Mulayam’s SP won’t go with Mayawati’s BSP and Chandrababu Naidu’s TDP would be wary of the Telangana Rashtriya Samiti. Equations at the state level would always play a role in the composition of the front.

If at all it comes into being there’s the crucial question of the prime minister’s chair. Mulayam’s ambition for the top job is known but what is the chance that other big leaders in the alliance would allow him the chance. As experience shows, such fronts end up throwing up weak prime ministers. Mulayam has a tough job on hand indeed. But the rest in the political spectrum need not sit smug. The third front could still emerge as a challenge.

That would suit Congress because it would help in stopping Narendra Modi racing towards 7 race course Road. By now, it is almost clear that the Congress party is gearing itself up to take over the role of a King maker by winning at least 100 plus seats. That means, it would create a situation where the Third front would have no option but to take the Congress Support for forming the government. In any case, the life span of such arrangements has been less than 2 years. That means, the Congress would perhaps allow the Third Front to remain in power till 2016 and then pull the rug.

But what if Narendra Modi storm into power on his own steam? The Congress party poll managers are aware that the people of India voted decisively for BJOP after Vajpayee government fell just for one vote only in 13 days. Then it became and government of 13 months followed by a full five years term.

If the voting pattern in Assembly elections during last 4 years is any indication, then the Congress party should fear the worst because corruption and price rise are the two factors where no one is going to touch the party with a barged pole. That may turn their worst fears into a reality in 2014 Lok Sabha polls.

(Posted on February 11, 2013 @ 10pm)

(Ajay N Jha is a veteran journalist from both Print and Electronic media. He is Advisor to Prasar Bharti. The views expressed are his personal. His email id is Ajay N Jha <ajayjha30@gmail.com> )

The views expressed on the website are those of the Columnists/ Authors/Journalists / Correspondents and do not necessarily reflect the views of ENARADA.